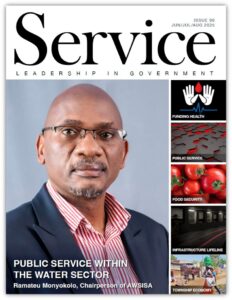

Opinion piece by Ramateu Monyokolo, Chairperson of the Rand Water Board and Chairperson of the Association of Water and Sanitation Institutions of South Africa

Water is considered a strategic national resource and is recognised as a constitutional right in South Africa. Nevertheless, the industry is experiencing a significant downturn. South Africa’s municipalities are drowning in debt. Non-revenue water averages 47% and consumer trust in public service delivery is eroding. Billions are owed to water boards, and the culture of non-payment continues to erode the foundations of water service delivery. At the heart of this challenge lies a critical policy tension: how to ensure sustainable cost recovery while protecting the poorest from exclusion.

The governance of South Africa’s water sector is distributed across various levels of government, with regulatory responsibilities shared among the Department of Water and Sanitation, municipalities, provincial departments, and the treasury. This results in overextension, disparities, and variations in standards enforcement. The current Water Services Authority (WSA) model allows politically governed municipalities to act as service providers, blurring lines of accountability.

As chairperson of the Association of Water and Sanitation Institutions of South Africa (AWSISA), I believe these challenges point to the absence of a strong, independent regulatory framework that enforces standards, regulates tariffs, and protects consumers and service providers. Regulatory independence is a foundational prerequisite for restoring South Africa’s water governance. Establishing an autonomous water and sanitation regulatory body in South Africa is imperative.

The unsustainable status quo

Municipal debt to water boards in South Africa has soared past R28-billion. Many residential and institutional water users either cannot or will not pay municipalities. The current system penalises honest payers, undermines service reliability and traps municipalities in a fiscal death spiral. Despite the constitutional obligation to provide basic water services, the financial underpinnings of this mandate are collapsing in the hands of municipalities.

Non-payment is often symptomatic of poor-quality services delivered by municipalities, eroding public trust. The trust deficit between citizens and local government is amplified by frequent service interruptions, billing disputes and a perception that payments do not result in improvements. Fraud, corruption and the presence of underqualified municipal officials only deepen this divide.

Trust is the cornerstone of any sustainable payment regime.

Additionally, municipalities receive various infrastructure grants from the national treasury to maintain and expand infrastructure in anticipation of population growth. However, billions of rand are returned to the fiscus annually due to municipalities’ failure to implement these grants effectively. This inefficiency feeds a broader narrative of mistrust, both in grant allocation and service delivery.

Cross-subsidisation and targeted subsidies

One approach has been to implement indigency policies and lifeline tariffs. While the principle of cross-subsidisation, which involves charging higher-income users more to support low-income consumers, is theoretically sound, its execution often lacks effectiveness. Targeted subsidies often suffer from misallocation due to outdated databases, political interference or administrative inefficiencies.

A reformed approach requires credible indigency registers, geospatial targeting and institutional insulation from political interference. Crucially, the indigent register ensures equitable delivery and enables the national treasury to allocate evidence-based, equitable shares and other grants to municipalities.

Behavioural economics and tariff design

Traditional tariff structures often assume rational economic behaviour, but trust and perceived fairness drive willingness to pay. Insights from behavioural economics suggest that simple, transparent pricing and visible service improvements incentivise better payment behaviour.

Several countries with comparable developmental contexts have established independent regulators. Examples include the National Water Supply and Sanitation Council (NWASCO) in Zambia, which uses licensing administration and performance reporting to enhance efficiency, the Entidade Reguladora dos Serviços de Águas e Resíduos (ERSAR) in Portugal, which monitors quality, pricing, and planning within a transparent and consultative framework, and the Water Services Regulation Authority (Ofwat) in the UK, known for its approach to tariff review.

In Kenya’s Embu County, pre-paid meters and community scorecards have improved cost recovery and user satisfaction. Brazil’s Sanear Programme embedded social norms and service visibility into its tariff strategy, yielding higher collection rates in low-income areas.

Inclusive, participatory cost models

Trust is the cornerstone of any sustainable payment regime. Community engagement – through participatory budgeting, water forums and user committees – can help co-design cost models that communities believe in. In eThekwini, South Africa’s early success with pro-poor water delivery was driven by transparent communication, credible enforcement and ongoing dialogue with community structures. Rebuilding trust will require political will and consistent institutional behaviour.

Regulating the tariff value chain

There is a lack of consistent and transparent oversight regarding tariff setting across the entire water value chain. The Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS) sets its own tariffs without any external regulatory oversight. In contrast, water boards adhere to an extensive consultative process that involves municipalities, the South African Local Government Association (SALGA), National Treasury, and DWS.

Rebuilding trust will require political will and consistent institutional behaviour.

Municipalities determine their tariffs independently, lacking oversight or regulatory standards. The national parliament’s role in tariff determination is ambiguous due to the absence of a guiding legal framework. This fragmented system leads to inconsistent pricing, institutional mistrust and inefficient service delivery. Additionally, unilateral high tariff increases by municipalities, without oversight or justification, often conceal underlying inefficiencies and fragmented capacity gaps.

Groundwater solutions for informal settlements

Groundwater solutions for informal settlements

Infrastructure and service challenges are especially severe in informal and low-income peri-urban areas. One of the most immediate solutions is to expand groundwater access through boreholes and related technologies. These interventions reduce the need for costly infrastructure investments and can deliver potable water without the traditional systems’ heavy purification and distribution costs.

Tariffs in these areas can also be lower, reflecting the reduced operational burden and promoting affordability. Addressing the needs of informal settlements with innovative, cost-effective solutions will be critical to closing the trust deficit and extending dignified water access to all.

From tariffs to trust

Reforming cost recovery in water services to serve impoverished communities is not solely a technical or financial task but a crucial governance requirement. A trust-based, equity-sensitive approach that integrates behavioural insights, community voices, targeted support and regulatory consistency is more likely to yield sustainable outcomes.

The time has come to move from punitive enforcement toward participatory partnership. AWSISA will continue advocating for regulatory frameworks and funding models that advance equity and sustainability.

Ensuring equitable access to water and decent sanitation requires a paradigm shift in the delivery model.

The case for an independent regulator becomes even more urgent when seen through the lens of cost recovery: predictable policy, credible enforcement and institutional fairness are vital to restore trust in the water sector. An independent regulator would provide technical continuity and depoliticised oversight, ensuring a consistent application of water laws and performance standards.

Ensuring equitable access to water and decent sanitation requires a paradigm shift in the delivery model. Water governance in South Africa demands a shift from decentralised discretion to institutional integrity. AWSISA proposes a partnership between municipalities, water boards, and the private sector through a special purpose vehicle (SPV). This aims to establish future utilities, ensuring water security.

Read more about AWSISA in Issue 90 of Service magazine: