By Schroders*

The circular economy is a change in the economic system. It means moving away from “take-make-waste” practices, where we buy, use and discard things. Instead, a circular system is one where products and materials are kept in use and production follows a sustainable path that reduces the consumption of raw materials.

The key aim of the circular economy is to decouple economic growth from virgin resource consumption. The simple reason is that the world is running out of resources.

We already use 1.7 times the resources that the planet naturally regenerates each year, and this figure will grow as the global population expands. We are living way beyond our means.

We already use 1.7 times the resources that the planet naturally regenerates each year, and this figure will grow as the global population expands. We are living way beyond our means.

Why waste is a valuable resource

Waste is defined as “material or resources that are discarded, unused or considered to be of no value”. However, waste is but a lack of imagination. There is very little “waste” in the modern world that is of no value; it is more about having the right infrastructure, regulations and will to capture that value. This gives us hope that we can improve current waste management practices.

On a global level, we currently sit at a powerful intersection of forces – affordable and efficient technology, supportive regulations and consumer and business demand – that will work to improve circularity, albeit at differing speeds at a regional level. There are many sources of waste. In this piece, we will focus on municipal solid waste.

What is municipal solid waste (MSW)?

MSW is rubbish from households or businesses (restaurants, hotels, offices). It typically consists of papers, plastics, discarded food, garden waste and other discarded items. The world generates c.two-billion tons of MSW annually. This is the equivalent of 111-million rubbish trucks per day. As economies and incomes grow in emerging markets, this number increases rapidly.

By 2050, with a global population of c. 10-billion, it is expected that the world will produce 3.4-billion tons of MSW annually (a 70% increase from today). This, however, doesn’t tell the entire story, as averages often hide the underlying dynamics. On one end of the spectrum, you have the North American region with c. 530kg per capita per annum and at the other you’ve got 168kg per capita in Sub-Saharan Africa.

The issue therefore is that if everyone in the world produced waste at the same rate as the average person from North America, then global waste production would hit c. 4.1-billion tonnes pa (or 210-million rubbish trucks per day).

The best way to reduce the negative impacts of landfills is to avoid using them.

Waste generation per capita is very highly correlated with income levels. It is a problem if we cannot decouple economic growth from resource consumption. Countries low on the income scale have ambitions to move up, and it is these countries that tend to see the highest growth in populations as well.

Why is waste a problem?

The biggest issue is how waste is disposed of because that can generate negative impacts on climate change, pollution and biodiversity. There is also the issue that by not properly recycling our waste, we create demand for more virgin resources when we are already over-consuming.

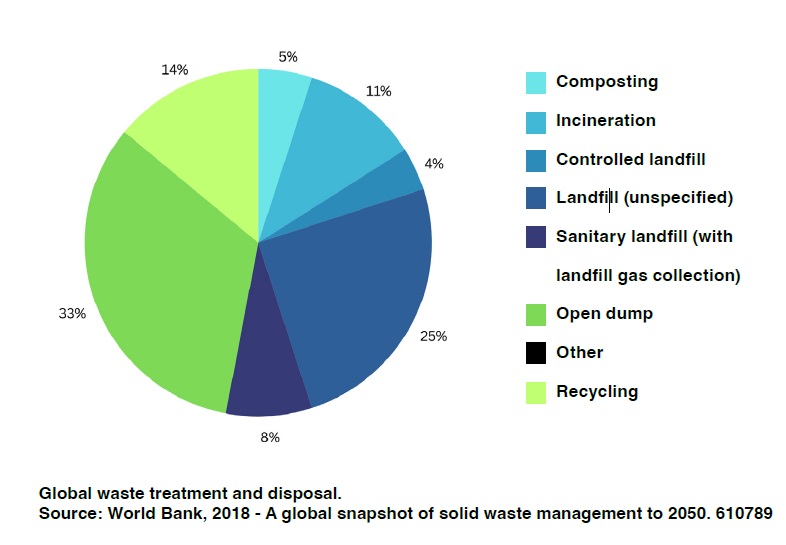

We can see from the chart that most waste globally is either openly dumped (c. 33%) or landfilled (c. 37%) with only 19% being either recycled or composted. About 11% of waste is disposed of via incineration (known as waste-to-energy).

Landfills alone account for c. 8% to 10% of human activity-related greenhouse gases via the release of methane gas as waste decomposes. This is before considering the other negative externalities like water pollution, soil degradation and the impact on local wildlife and biodiversity. There is also the issue of resource wastage, as a lot of what goes to landfill is of value.

The best way to reduce the negative impacts of landfills is to avoid using them. However, this isn’t always possible. The next best thing is to ensure that the methane emissions aren’t released freely into the environment. There is increased focus in regions such as the US for this approach by capturing these landfill gases and converting them into renewable natural gas.

Regulations are forcing change in the industry

We see increasing “polluter pays” regulations to increase the costs of poor disposal methods (eg landfill). There is also the further development of “extended producer responsibility” across many waste sectors, which puts more of the burden of the cost of physical collection and disposal on the producer.

For example, the roll-out of deposit return schemes across the EU and parts of the US will help to improve recycling rates for single-use containers (eg plastic bottles, aluminium beverage cans).

For example, the roll-out of deposit return schemes across the EU and parts of the US will help to improve recycling rates for single-use containers (eg plastic bottles, aluminium beverage cans).

A lot of regulation aims to either reduce waste at source (ie by being more efficient) or to increase the use of recycled, recyclable or bio-based materials. This is creating a supportive regulatory environment for companies that can supply products based on sustainable biomaterials or ones that can offer a high degree of recycled materials.

We’ve also seen countries like China implement bans on the import of certain types of waste to ensure they are only importing higher-quality waste streams. No longer can countries as easily “export” their waste problems.

These factors result in the need for more developed waste management infrastructure in much of the developed world, with a particular emphasis on recycling capabilities.

Locally, the amended Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) regulations, which became effective in late 2020, require manufacturers and product importers in the packaging industry to contribute towards the recycling of product packaging, with a significant impact on waste levels thus far. One area yielding positive outcomes has been the implementation of a 50% organic waste ban to landfill in the Western Cape, which is set to rolled out countrywide by 2027 and further increased to 100%. According to a recent article, the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment has included the ban as part of the licensing requirements of the landfill, to ensure compliance.

A $1.3-trillion investment opportunity

As investors in the circular economy, across both the listed and private markets, we recognise the enormity of the challenge that the global economy faces in changing our linear waste management practices to more circular ones. However, we are extremely excited by the significant investment opportunities arising from this challenge.

As of 2022, the global waste management industry was valued at $1.3-trillion and is expected to grow significantly over the coming decade.

The expansion in both recovery and recycling is creating growth opportunities for companies across the industrial spectrum.

*Authors: Jack Dempsey, Fund Manager, Paul Lamacraft, Head of Sustainability Private Equity and Samuel Thomas, Sustainable Investment Analyst from Schroders.